Daniel Libeskind: Architect. (July 2007, Shediac.) According to philosopher Aviezer Tucker religious miracles as historical ‘events’ must be preposterous fakes. Hebrew for ‘miracle’, nes, also signifies banner. Miracles have always served as the highest form of marketing. Yet one needn’t concede that such events are bereft of inscrutable qualities.

In Berlin, in September 1991, I walked along the space until recently occupied by the Wall. A gypsy circus had set up in the scrubby field by the new National Library. By intuition, I wandered from there along the line of the effaced Wall towards the Martin Gropiusbau, then nearing the end of its splendid restoration as an art museum, the gilt frieze shining in late afternoon sun.

Approaching its sober facade, I encountered a Japanese sculptor’s massive horn composed of loose black timber laid across a circular plaza. The sculpture distracted me for some minutes while a new feeling took hold, a definite sinking feeling.

Becoming conscious of a weed-infested fence, with a rusted, sealed gate on my right, I felt mild panic and then stomach churning as I ventured further to turn that corner. Only then did I understand I’d arrived at the former SS headquarters.

Visitors touring the temporary museum erected on its ruins were almost entirely German. The exhibit’s theme was atrocity, including Russian atrocities towards Germans in 1945. The capacity crowd shuffled through wordlessly, with rapt detachment. In the basement giant sinks had survived the Allied bombing. It was impossible to hold back tears facing the portraits of young Germans who’d resisted the Nazis and died at SS hands in that cellar.

Breathing deeply, I retraced my steps, entering the Martin Gropiusbau—Italian Renaissance mingled with Arts and Crafts—meticulously restored from near annihilation during the war. Noticing a card in the lobby indicating rooms above housing Berlin’s Jewish Historical Museum I made my way to the uppermost floor, completely alone in a heavy quietude. An elderly custodian answered my bell ring, unlocking a tall door so I could spend an hour among the artifacts of Berlin's prewar Jewry.

In the early 1980s producer Ted Demetre screened Fassbinder's Berlin Alexanderplatz, all fourteen episodes, in a single marathon showing at the National Arts Centre. Along with Lanzmann's Shoah, these Canadian premieres shaped my perception of Berlin. They can’t account for my intense somatic premonition of that place soon afterwards named the Topography of Terror.

... (December 2011, Berlin.) The collection of Herr Wagener, a nineteenth-century banker whose art collection formed the nucleus of Berlin’s national gallery, is striking for its literal, parochial and stoic romanticism. Glum lighting accentuates the ponderous atmosphere in the paintings. One sees how readily so much twentieth century art was perceived as ‘degenerate’ against this background.

The room devoted to Caspar David Friedrich discloses a manifest destiny encoded in the entire project: a descending darkness, solitude among ruins, an elegiac aesthetic in advance of events.

...Walking north on Brunnenstrasse up to the line of the former wall where one inner section stands among sleek hi-tech interpretation panels. Still, a sad intersection. Then by U-Bahn to the Jewish Museum.

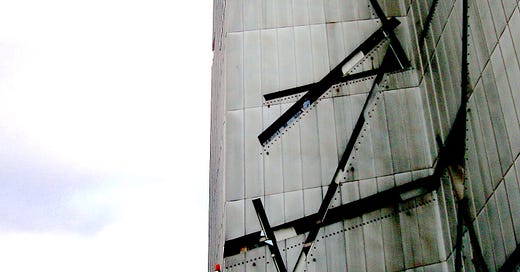

Daniel Libeskind’s jagged and scarified edifice seizes one’s attention, bucking what appears to be the museum’s softer mission to re-integrate Jewish memory into German society. Its core collection remains the very memorabilia I’d seen at the Martin Gropiusbau in 1991. That day I was the sole visitor; today this large building was jammed with people.

Libeskind’s knife-slashed facades dramatically fenestrate cool interiors, but the Holocaust Tür is his most striking intervention—a vertical angular void with the merest hint of natural light far above. How the slightest opening of a window can completely alter an atmosphere.

...onward to Mies van der Rohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie, his last (finest?) building, opened in June 1968. A design generous to the art. The sunken sculpture garden harboring Germany’s ‘soiled mother’.

...to the Schiller theatre for L’Étoile, Chabrier’s peculiar light opera with dark tones, a high-camp diminutive king oddly resembles a figure I’d dreamt of. Caspar’s full moon followed us everywhere, was up all night.

...to Peter Eisenman’s Holocaust Memorial, its subterranean visitor centre, superb, moving, all undertow. In a discussion with the Memorial’s clear-eyed director, Dr. Baumann: founder Lea Rosh’s fortitude, the vicissitudes of such a commemoration, its impossibility, really. And yet, Eisenman’s terrain of concrete stellae—set at strict intervals of 37 inches, the human temperature, with a strange acoustic—typically disturbs the children on school visits. Dr. Baumann hears their heightened voices. “You must have an international design competition for Ottawa,” he advised.

...through the old Jewish Quarter on a long tram ride into East Berlin. Once outside the core the urban landscape soon becomes austere. Shopping and sketching the Alexanderplatz Christmas market. And now a hiatus at the Grand Westin with martinis, waiting for Carmen at the Oper Komische; above us, lengthy orations in honour of a certain Dr. Hetzer’s retirement; at the head of the mezzanine staircase, three tired girls slumped in winged angel outfits. (December 2011, Berlin.)

... (February 2014, Ottawa.) With the National Holocaust Monument jury all day, the boardroom packed with jurors and advisory committee members. Larry Beasely in the chair. Presenters, the six shortlisted from an impressive international roster, understandably were nervous in this formal atmosphere. Off the top, Gilles Saucier made the best of his twenty-minute allotment. Esther Shalev-Gerz, brilliant sculptress of the ‘sinking’ monument against fascism in Hamburg, proposed a spherical form beneath which visitors would deposit stones.

The jury was absorbed by the intellect and imagination of Julian Bonder and Krzysztof Wodiczko. Ron Arad presented a joint scheme developed with David Adjaye, the latter away on his honeymoon. Beguiling in a wide floppy hat, Arad mesmerized the assembly with a wry explication of their finned structure.

Daniel Libeskind, clearly a leading proponent heading into tomorrow’s final deliberations, was at once charming and forceful in presenting his ‘exploding’ Star of David as a journey through the star. Old hands muttered darkly of budget risks. Wisely, Libeskind addressed Raymond Moriyama directly about the monument’s crucial relation to the latter’s adjacent war museum. It is key that Raymond agreed to sit on this jury.

Worries that a ‘starchitect’ might grant little personal attention to a monument design attenuated as jurors witnessed Libeskind warmly engaging the public around his maquette at the vernissage. In fact, his wife Nina (also present) is originally from Ottawa. They were married here at about the time her father took over the NDP from Tommy Douglas.

Harold “Hesh” Troper. Historian. (February 2012, Ottawa.) A gathering today of twenty or so political staff and bureaucrats at the Department of Foreign Affairs to discuss the National Holocaust Monument. I’m shocked at their levity. Flippant whispers between the officials deride the project as Minister John Baird’s pandering to Israel. This group, in their twenties, a few in their thirties, have but a basic knowledge of the Holocaust; they assume Canada’s ‘multicultural ethos’ goes all the way down. My suggestion of a consciousness-raising history workshop is accepted, so long as I organize it at the National Capital Commission.

…Historians Hesh Troper and Doris Bergen are up today from Toronto to lead the session. Doris: “you see, the Shoah was a state-systemic phenomenon implemented by officials and academics rather like us.” Hesh, on the Canadian dimension, recounts how he and Irving Abella pursued archival research for None is Too Many through wartime and post-war records, always expecting to find the turning point in Canada’s harsh exclusionary policy: 1938? 1940? 1942? Surely by 1945…? No, not before 1948 did any restriction ease on entry of Jews to Canada.

Following their book launch thirty years ago, a woman roused Hesh in the early morning hours. She’d read it non-stop, cover-to-cover. During her entire adulthood she’d been guilt-ridden that her family hadn’t done everything to bring relatives fleeing the Nazis to safety in Canada. Some savings were withheld to pay for her education. She’d called to thank Hesh because None is Too Many had reassured her that nothing, certainly no amount of money, could have swayed the grimly antisemitic Canadian authorities under Mackenzie King. As Hesh concludes, a long silence settles around the table.

Berlin. A city like no other. -- I had hoped when first there to see the Berlin Wall. To see it. Naive me. It has vanished entirely except for a few blocks of cement here and there. During my last visit, a giant diaroma had been constructed in an enclosed exhibit to mimic what the very street outside would have looked like before the fall of the wall. -- Put another way, one may visit Auschwitz -- there are remnants enough to make the visit a bizarre but somehow "educational" tourist site (I do not say attraction). But the Wall is gone. -- It introduced me to the thought that the destruction or obliteration or annihilation of the offending thing (thing here as something that might have had a monumental afterlife) ironically makes it infinitely harder to recall or commemorate the offending thing. Between the desire to erase the object that recalls atrocity and the desire to preserve that object as a means to recall it so as not to repeat it, where does one land? I suppose no general rules are applicable... like most things, one would have to decide case by case... But I will say that I wish they had preserved more of the Berlin Wall. Its absence makes the reality of its as historical past ... less real. As usual, a stirring and searching post -- MK has a gift for the elegaic, I think -- not unsurprising in a context where one principle is "we study history to honour ancestors" [Post #4].